We are about to release another eBook, a sequel to another, a trilogy which we packaged under the cover design at right. Composing from our three hardbound books by a serialization fanned out above, being of the common title Cephalos Ward of Eleusis, Books I, II, and III, the joint venture Publishers have released since 2012 advanced maritime prehistory of earliest. Greece from 1405 to 1360 BC had the Isthmus and the Saronic Gulf Rim Powers orchestrated their shipwrights and many landfall slipways into an effective league of commercial maritime sponsors. The serialization is a pioneering book project of a style we call academic prose fiction. We think ourselves at proof that it remains the best and easiest means to a through education of how the Pre-Hellenes of the 2nd millennium BC became the earliest Greek ethnicities, and how their young meld pointed the way to two more by Iron Age Greece that produced the Ancient Greeks’ Classical Age Geography. Books IV and V have been left out, but they will comply with an evolved naval and mercantile focus upon two major sea engagements — devastating sea battles each and again directed against Imperial Minoa of Crete Island in 1365 and 1362 BC. They shall take a theme of covert strategic revenge, in redress against an even more vengeful imperial Minoa which was compelled to exceed herself. Because most prehistorians do not agree that such conflicts were ever enabled by Cephalos as a strategic navarch, or per se as a true person of historical composition, I continue to call all released books about him patently fictional, allowing that even a mythic personage could speak for an entire millennium’s conclusions.

Each book in series a proto-history by special determination upon a narrative genre wrought in oldest time and places, there’s a need to review the eBook Trilogy. It serves the whys and wherefores of genuine prehistory even if least rigorous: Lay person readers who are new to our Bardot Blogging until 2020 deserve a succinct understanding of robust historical accuracy. Faithful readers of the entire serialization shall enjoy the reviews a process of considerable enhancement of novelty, while an overview of a lifetime which the Ancient Greeks wanted expunged for absurd reasons that our venerable humanities scholars still adhere to wrongfully.

Where Our Bardot Books began:

First, there’s our dependency upon mythography by Classical Greek Mythology, despite that it greatly constrains book authorship by S W Bardot as a poseur and translator of a fictional Bronze Age author — Mentor son-of-Alkimos — at firmly inhabiting the times and places which concluded the Late Helladic Period of Greece. The Publisher, we remind, started with the reign of Kekrops in dotage and death in 1405 BC. That mythography postured two King Kekrops of Attica alive the 15th century BC. Ancient Greeks have proven as wrong as any Classical Greek Mythology ever written can be. And so, I have conflated away the first, or legendary, Kekrops, as a make-believe dynast and patriarch in order that the singular Kekrops proves out as a champion of a quintessential hallowed matriarch who aspired for their co-regency together. The dynast and patriarch never actually existed, but our Kekrops had three brothers and a brother -in-law who coveted what that matriarch, Metidusa, wrought by the one King, their brother Kekrops, just before he died of his dotage in 1399 BC, after being deposed for certain overzealous reinstatements of Attica’s oldest and ancient revered beliefs. A very popular sovereign to his very end, even so, so, too, was his sacral wife by Eleusis, the “arch-widow” Metiadusa, who lived on as the entitled Diomeda, or High Sister of Grace, over a special teaching sanctuary by a great teaching order of priestesses who preceded her.

The contrived duplication of a sham legendary House, as somehow conflated with a true branch royal house by the patriarchal dynasty attendant the Attican House of Erechtheus need never have been. Thus there was no need either for two scions named Pandion, successors to respective Kekropses, or two lovely daughters, or much younger sisters named Herse. The legendary maiden of the two was never seduced by the God Hermes because that future Olympian deity didn’t exist yet; he was only the God of Cairns, of pathmarks duly disclosed to heralds and couriers under dispatch of their illiterate principals. So our eBook allow a very able and true son Pandion was born to young marriage around 1430 BC. The young and frothy marriage of Kekrops and Metiadusa suffered for her many miscarriages subequently, until she finally bore a daughter, Herse, late in life to become her heiress, or successor to a foremost hereditary sacral majesty known by 1405 BC. Metiadusa, abdicated her title of Diomeda to Herse in 1388, when the daughter was only fifteen. Over the years since she’d been born, moreover, the Fates would have little Herse spend her girlhood mostly in Attica. There she became a high priestess for both Eleusis and Attica, until attaining as a foremost teenaged princess over the Atticans as well. Indeed, excepting only one other dynastic daughter by patriarchy, Prokris of the acclaimed House of Erechtheus, Herse was amply compensated by the special adoration of the Atticans and Eleusis for her very special and most brilliant gifts of mind and memory. Too, she had the cardinal virtue charis, meaning the selflessness to shower back upon her menials what they afforded her of utmost exaltation. At sixteen, concomtitantly, the Trials-at-Bridal for her were held, as between suitors invited towards marrying her with possibility of a lifetime consortship happily ever afterwards.

Herse stood communally as a nymph, or dynastic bride of the very first worth. There was never any need to make a legendary sham of her parentage, of her hereditary stature, of her ultimate sacral maternity of a single child Cephalos. No need, either, for his paternity to be made a sham of misplaced grandeur imposed upon a foreign husband to Attica via his martial prowess to prove a Kerkyon, or greatest champion-at-arms, which Eleusis fielded martially and selflessly, as behooved him to prove how he could with utmost satisfaction of special persons to his heart and precocious mind. And yet the Ancient Greeks never could take him either for his true illustriousness amidst the highest potentates of north mainland Greece.

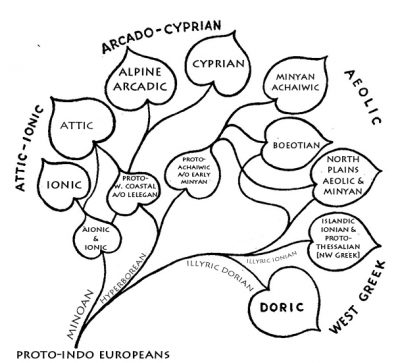

The postured Kerkyon was Herse’s taken husband Deion. He was already a champion-of-arms out of the Low Midlands of north mainland Greece, [long before they became constituted as Boeotia]. The Ancient Greeks never got his ethnicity either, as both a Phocian and Kadmeian. In his boyhood he showed off most promisingly of martial ilk, whereby adopted into the champion men-at-arms in fealty to the Kadmeians. He was brought up to fight under their High Prince Labdakos, becoming a champion skirmisher at prowess of many light weapons. He was so natural and versatile a great leader that he soon proved a master strategist over all light forces-at-arms of the Kadmeians. Under that cited liege warlord and sovereign, he moved into his twenties as constant to offensive vanguard, while achieving major defensive repulses of predatory Minyans. That enemy nation race of horse peoples had been conquering the north mainland above the Low Midlands in many piecemeal fashions. Labdakos became High King of Kadmeia for drubbing them, but only briefly at the regal title after a prolonged lifetime wherein he was compelled to be solely a reputable roving warlord unjustly disabled from rightful royal succession by two imposed oligarchic regencies who blocked him from supreme ascension. I will not explain here how: Suffice to say in review, at a date uncertain around 1410 BC Labdakos triumphed at a severest rebuke of the Minyans under special vanguard strategies of Deion. The warlord strategized rearguard deployments of heavy champions-at-arms and -at-cart (chariotry) under his junior heir, prince Laios, the High King’s son. Deion drove back the Minyans to the High Plains, future Thessaly, while Labdakos regained and revived all low country plantation matriarchates of Kadmeis along the vast Asopos River Valley which runs flay low country to thesea where future and most famous Aulis situated. Alas, just as he ended his campaign season by full regain of those Lands of Aegina, the Minyans hazarded a final resurgence directly against Laios the son, to occupy anew her hallowed person’s landed inheritances. They mangled the Kadmeian rearguard and humiliated Laios. A shameful defeat after a time of immense regains, the Kadmeians were compelled to rest at arms indefinitely, thereby to restore themselves to the imperial strengths that Labdakos and Deion might have enabled them, had he not died only a few years later, in the early 1380s BC.

Deion easily retained his repute and highest standing as a formidable martial-at-field, especially over major force deployments of royal Foot Troops against heaviest Horse and Chariotry. He was compelled to retire to Dauleis to serve the Matriarch Lebadeia of Phokis, after Labdakos could no longer stand him an army of elite warriors. He had no wonderful princess to court conveniently either; or he did not until he received invitation from roving proxies of Metiadusa who bade him come down to Eleusis, there to prove victorious at the trials-of-bridal conducted for her daughter Herse as recently ascended to her the title Diomeda. The newly instated Diomeda presided a rich sanctuary principality (as Eleusis veritably was, besides being also an Attican protectorate who greatly needed a superb martial-at-arms. Deion won over all rivals easily and proved most winsome to the sixteen year old bride. Their effusion of passion from each other rendered a first son soonest and and easiest of delivery. They named him Cephalos, “Brainy,” upon his first birthday, 1388, after his brilliant year of infancy. (Bronze Age Greek babies began aging, sometimes very ably and precociously, from the date and year posted after their natal deliveries).

The Ancient Greeks kept on goofing by making deliberate mistakes about Herse’s husband and entitled Kerkyon, Deion: They had him born to a earliest patriarch named Aeolus as the fourth, perhaps fifth paragon son who would form up and rank as a strategos, or general. Five martials-at-field vied for their exiled matriarch Aegina. She dwelt Oinopia Island within the Saronic Gulf, in good view from Eleusis, reposing there as a refugee from her beloved Asopos River Valley. Driven offshore by the Minyans at their resurgent martial occupation, many other Aionian mothers of sons of Aeolus, a polygamous mythic personage thus believed, pledged themselves in fealty to Aegina — and ultimately to her precocious son Aiakos (he’s most often spelt in Latinate Greek, as Aeacus, which orthography I refuse to use). Their sons would regain all that such powerful matriarchs, the former governesses over vast plantation agronomies, had lost to the Minyans.

That regain began when Aiakos was fifteen years old and had become a stupendous prodigy under his mother’s tutelages. It took five year s into the decade of the 1390s to accomplish his mother Aegina’s full restoration as a greatest Aionian over a low country ethnicity that sprawled along the Strait of Abantis (later Euboea.) Deion would again win all vanguard tests of arms, for her and Aiakos, before his son Cephalos was enabled oldest friendship in their respective early manhoods. Although their mothers were close and of mutual highest sacral elities of womanhood, they least rewarded each other despite Deion’s most apparent strategic genius. He was also became fated to lose Herse in marriage when their marriage no longer delivered children that justified their wedlock as a lifelong consortship. For a barren marriage, once proven as such after 100 solar months, a Great Year, became devoid of any new progeny after Cephalos. Deion was, in fact, virtually divorced from Herse earlier, when he took up as martial-at-arms to concert all of the petty chieftainates and realms conjoined to Attica upon the Saronic Gulf. For once acquitted at that, thereafter he left the Low Midlands, too, forever to dwell within the High Plains, which, before their common dub as Thessaly, bore the toponym of Great Kingdom of Minya after the reconquests of Aiakos which we’ll review in the next Bardot Blog review after this one.

Let’s pause here to consider how rapidly paced I’ve been at review of the prelude book about Cephalos and his parentage. Clearly, the review by all of the above events and developments has required a deep immersion by audition, a full dunking by the reading too, whereby by a hearty and rich soup of offered contexts about powerful men and women of a mythic and mostly lost pasts. That momentousness is why I’ve spooled my proto-historical biography of Cephalos coming-of-age over three books, leaving to a last two books his early paramountcy as a naval genius — one duly paramount over an entirely new era of great oared vessels, especially those of warship classes. As we’ll move into their contexts, moreover, I shall prove at times equally dense. That’s why proto-history, my own preferred genre of historical fiction so nil of novelistic bents, is so ideal as a pedagogy that teaches of all the earliest Greeks who were forming up as distinct ethnicities, and yet ever onward towards their making of a great Bronze Age civilization that would vie so readily with many others developing abroad the Eastern Mediterranean and other very young and contiguous Seas.

Why we’re great Teachers of the Pre-Hellenes and Earliest Greeks who composed from Them:

The Ancient Greeks have proven inept, or at least unreliable over the centuries, about the father Deion. He has had to come through our serialization of Books as a Chief of Wardens over all the coastal realms upon the Saronic Gulf during the 1390s. That title means he was a chief over consorts lord protective of outstanding rural matriarchs coastal living inland the Saronic Gulf and Cretan Sea. He proved sutied to tulutuous events and developments. As soon as his marriage to Herse for a Great Year, for instance, his brother-in-law Pandion was deposed as High Chief of Attica at only 38 years old, despite he was the dynast of the House of Erechtheus. That son-of-Kekrops had to return cowed to the homeland of his wife Pylia, to whom he’d been married as her consort home protector of the realm Alkathoos. It lay just west coastally of the Eleusis and shared the Eleusis Sound of the Saronic Gulf. Pandion became a great man there, by serving all matriarchal governesses of the Great Isthmus of Ephyrea (before it became Korinth and Megaris during the Archaic Age of Greece). Pandion from there was always stalwart for Deion, and stubbornly his subordinate, but the good brother of Herse could not allay the consequences to her barren marriage.

That barrnenness wasn’t the only estranging issues that breached what started off as bright and hopeful royal wedlock. Herse and her mother were firmly loyal to Crete’s imperial House of Minos, as were most mainland matriarchs, whereas Deion was dubious about the ruling Minos Lykastos, who he suspected was losing his grip upon an oldest and greatest ever sea empire (a thalassocracy), that of Imperial Minoa since 1600 BC. In his boyhood the Cretans were becoming seriously suspect as ruinous of the great maritime commerce of their liege sovereign. Crete was still under repair of its serious losses of ships to the volcanic eruption of Thera, a largest island of a group of isles, circa 1505 BC. That cataclysm had so weakend Crete herself that she was conquered by Argives and Anatolian Karians (who called themselves Millawandans of Anatolia across the White, or much later Aegean Sea. The Minos at Cephalos’ birth was the great grandson of Cretans best described as hybrid pre-Hellenes to both primordial Crete and Argos. His immediate forbears were excellent Thallasacrators, or sea emporers, who brought Crete back through her cartel relationships with the Levantines of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Egyptians, or Nilotians, of a great desert empire capped by an immense deltaic region offering maritime surpluses. The Argives had lapse concomitantly since its invasion of Crete, despite their great dynasty achieved through the progeny of the famous Perseus and Andromeda over all the Southland of Greece since 1590 BC. The north mainland divorced itself from Crete altogether, to face down new enemies nomadic by arrivals from the north, or along the North Rim Sea of the Cretan White Sea. The reason for such seccession has never come clear, we admit, but we think it may have been due to higher incidents of piracy along the Cretan mains within that sea, and the primary instigator was the Minos Lykastos’ heir apparent, nameless except for his princely title of Minotaur, albeit not to be confused with the much later mythic personage of that name.

Whatever the instigations, Deion learned from seafarers and active shipwrights upon the Saronic Gulf that the most admired Lykastos had lost control over his far fleets under the commodoreship of his son, also the husband of the Euryanassa Pasiphaea, the Empress of Crete who actually superceded that man despite he was the Minos.

Herse was also inculcated with her own worst prejudices, against the Kadmeians and Minyans who would conquer and exploit all the lesser powers of the north mainland. Deion realized her ingrained hatred of the Kadmeians, to whom he’d been of outstanding service, and of the Minyans whom they mutually loathed. Pandion had been deposed by his brothers, who consolidated their patron clan powers over the Lower Peninsula in order to usurp them, under the active agency of High King Labdakos. Pandion held no grudge towatds him, however, for knowing that Labdakos had bribed him despite his refusal of any cajoling that would have conjoined barely unified Attica to the High Kingdom and quasi-imperial confederation of the Kadmeians. Instead Pandion insisted that he martial and mobilize all the consort home protectors of female rural governances into a mutual defense, or sometimes obligatory repulse, of both Labdakos and the Minyans. At that he should have won the love and pride of Herse in him, her own consort by title of (The) Kerkyon of Eleusis. But he did not because Herse p[roved pig-headed against her brother and her husband. So woe to her that she lost a man who greatly impassioned her to temporal disagreements that eroded their marriage away, even as barren as it also proved.

I cease at review of Cephalos’ parentage and his infant and toddling years. His boyhood until had attained age of nine years old (when he was really aged ten). For by the end of that boyhood I have much more in review to summarize and succinctly explain by our next Bardot Blog.

August 10th, 2023, b y pseudonym of the Publisher, R Bacon Whitney

August 10th, 2023, b y pseudonym of the Publisher, R Bacon Whitney

You must be logged in to post a comment.